Children’s literature is full of scamps and rascals, loveable troublemakers whose disregard of the rules endears them to us and shows us what adventure there is to be had in misbehaving. Max would never have made his way to the world of the wild things if he hadn’t first been sent to bed without dinner. There’d be little joy in watching Eloise sit obediently in her hotel room. Bravery blooms when characters choose to bypass what’s expected of them in order to do what they want to do.

Yet parents around the world sometimes find issue with these portrayals of rambunctious kids making trouble. What kind of lesson, they ask, does a child reading such books learn? Are we encouraging the youth of America to rise up, neglect their chores, ditch school and become underaged outlaws?

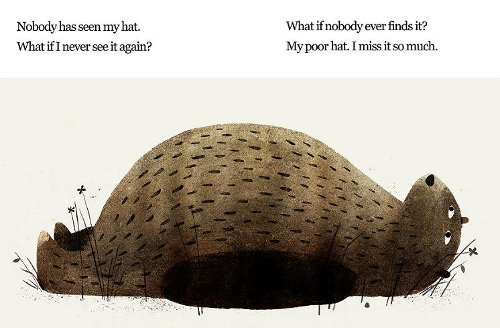

There’s no clear answer to the ethical dilemma such books may pose. Just take Jon Klassen’s I Want My Hat Back, a perfectly friendly tale of a bear searching for his lost hat. The bear goes through the forest, politely asking a variety of forest creatures if they’ve seen the missing object, until he meets the rabbit who has, in fact, taken the hat. The bear eats the rabbit, which is not such an unusual end, if you consider the laws of nature.

But some parents found the conclusory killing to be more violent than natural. As one Amazon commenter wrote:

“This is a story about a bear that kills a rabbit out of revenge, not because he’s a hungry predator. And it’s a hilarious ending because that’s the last thing you would expect in a book for children. Because that’s the last thing that belongs in a book for children. The message here is, “Don’t touch my stuff or I’ll kill you.” Pretty much the opposite of what you spend endless hours trying to teach little kids, if you want them to get along with any other kids.”

The New York Times, reviewing Klassen’s follow-up, This is Not My Hat (this time a small fish steals a big fish’s hat), points out that the small fish is entirely upfront about his crime, more concerned with pulling off his caper than with right or wrong. They concluded that the message might be either “a cautionary tale of either righteous class struggle or uppity proletarians,” depending on how you look at it. This is, probably, a more complicated moral lesson than might be expected from literature for the kindergarten crowd.

But children’s books shouldn’t be made to avoid complication in favor of clear-cut moral education. The best children’s literature often straddles a difficult line, not only morally, but emotionally, and psychologically. If you consider The Velveteen Rabbit appropriate reading for a child, you’re not only signing off on the notion that kids outgrow their stuffed animals, but on a whole panoply of hard-to-parse ideas about personal fulfillment, the value of hard work, and mortality. Just because young children may not have the words to break down a story into such lessons doesn’t mean they don’t, on some fundamental level, understand them.

TOON’s own Maya Makes a Mess, raised controversy on a gentler scale than murder. Instead, we found that some readers took issue with Maya’s unruly eating habits. Though the age of etiquette likely passed over 100 years ago, some societal guidelines remain. A young girl who likes to eat her pasta so that it gets all over the table, herself, and those around her, does not set the Emily Post standard for dining. But learning how to eat isn’t the only narrative the book presents — by bursting into a fancy dinner with her unique style of consumption, Maya manages to remind some fancy folk (including the Queen herself) that the point of food, and perhaps life, is taking pleasure in the everyday.

Children’s literature, at its best, doesn’t just tell children how they should be. It celebrates children as they are — messy, wild, unformed, insightful, instinctive, joyous and free. If these stories lead to more kids refusing to eat their peas, perhaps they also lead to more kids feeling empowered to be who they want to be. It’s hard to find fault with that.