William Steig was born 105 years ago today on November 14th, 1907. Though he’s best known as the author of beloved children’s books including Abel’s Island, Dr. De Soto, Shrek, and many more, William Steig didn’t begin writing books for kids until he was 61. This is not to say that he started drawing at that age — Steig produced over 2,600 drawings and 117 covers for The New Yorker after beginning work there in 1930.

His drawings for adults display Steig’s sharp, even twisted humor, sparing no one. Marriage, depression, greed, self-infatuation, and a whole host of other human faults are unerringly skewered by Steig’s pen. Using stark, simple pictures, he illustrates unfortunate human conditions, often with no more than a single image and a pithy caption.

This is not the Steig we know from his work for children. His picture books, like Spinky Sulks, or Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, bring us child heroes who are sometimes petulant and strong-minded, along with portraits of the parents who care for them deeply. His loose, colorful drawings convey the emotions of a fantastical circus as well as they do the wrenching loneliness of a winter night.

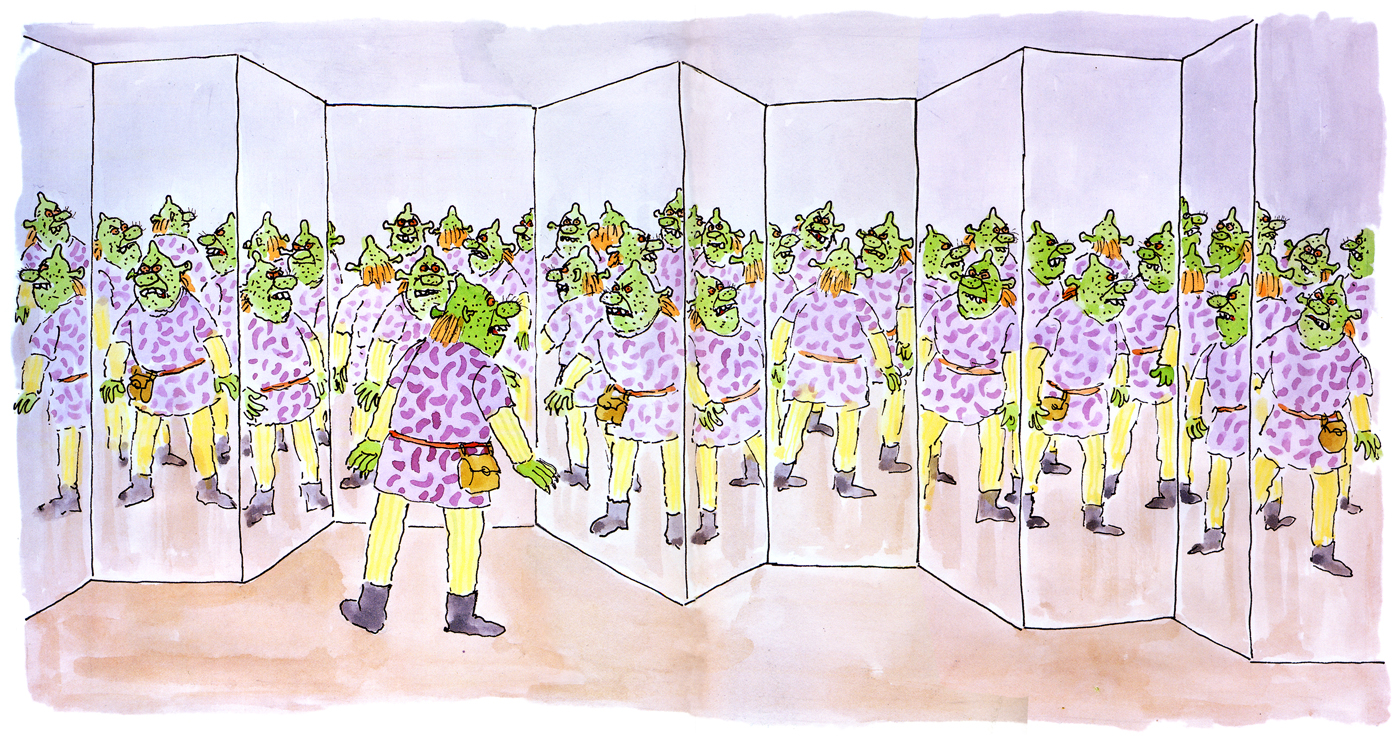

His original Shrek is a far cry from Disney’s version — in Steig’s book we meet a warty green monster who delights in scaring and disgusting others, is terrified by the idea of children and cute animals, and whose princess, when he meets her, is already a horrifying ogre. This is a story less interested in drawing a loveable, if hideous, hero, and more interested in making it clear that everybody, no matter their appearance or disposition, can find their perfect match.

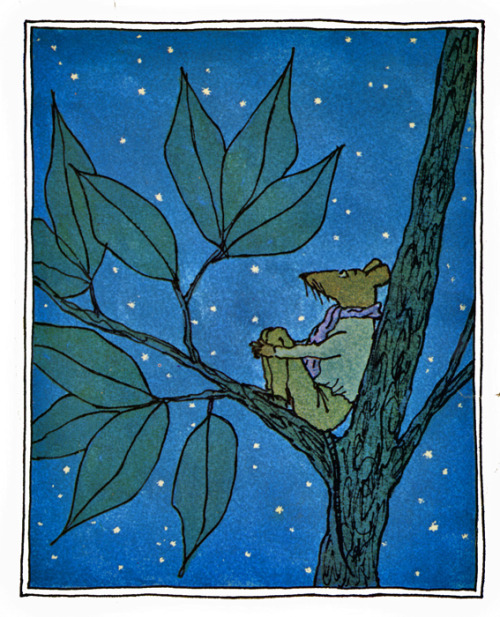

But any discussion of Steig’s work would be incomplete without calling attention to his prose in addition to his illustration. Consider the Newbery Honor winning Abel’s Island (a personal favorite), Steig’s tale of a mouse marooned on an island, far from home and from his wife Amanda, forced to survive in the wild. Here’s one excerpt, from a moment in winter when Abel begins to lose hope:

He became somnolent in his cold cocoon. In his moments of dim-eyed wakefulness he had no idea how much time had passed since he was last awake — whether an hour, a day or a week. He was cold, but he knew he was as warm as he could get. The water in his clay pot was frozen solid. His mind was frozen. It began to see it had always been winter and that there was nothing else, just a vague awareness to make note of the fact. The universe was a dreary place, asleep, cold all the way to infinity, and the wind was a separate thing, not part of the winter, but a lost, unloved soul, screaming and moaning and rushing about looking for a place to rest and reckon up its woes.

Steig’s respect for children is evident in his willingness to portray Abel in the depths of existential misery. And his ability to make such feeling so clear is proof of his talent.

Abel does, in the end, make it home. Steig didn’t underestimate the power of a happy ending.